Chicken of the Woods: Our first fungus genome

The Darwin Tree of Life project has published its first genome of a fungus: chicken of the woods (Laetiporus sulphureus). Our fungi-focused team at the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, take an in-depth look at this impressive woodland species.

Laetiporus sulphureus, commonly known as chicken of the woods, is perhaps one of the best-known bracket fungi in the UK. Its bright orange-and-yellow colouring catches the eye, standing out clearly against the bark of the trees from which it grows. It is thought to occur on a range of different broadleaved tree species in the UK, including oak, sweet chestnut, ash, cherry, and even yew. It is considered cosmopolitan, meaning it is found in many regions of the world, and has a long history of human use as food.

Currently, the genus Laetiporus includes 17 species, though this number is changing due to new discoveries and revisions to the way we classify them taxonomically. The genus is cryptically diverse – meaning deep genetic differences between species have no visible signs in their morphology. Globally, our understanding of this in America and Asia (particularly China) has recently improved, but in Europe cryptic diversity still remains understudied with only 3 species currently recognised.

The spore producing bodies are highly sought after by foragers, as they are easily identified and can occur in large quantities. When collected at an early stage these have a soft, fleshy texture and pleasant flavour, in some ways comparable to chicken. This fact, combined with the golden colouring, has led to the common name for this fungus, ‘chicken of the woods’.

Engineering ancient forests

There is, however, a great deal more to this fungus than its culinary value, as it is one of the key engineers of hollowing in veteran and ancient trees, particularly British species of oak — a role that creates microhabitats that are booming with biodiversity.

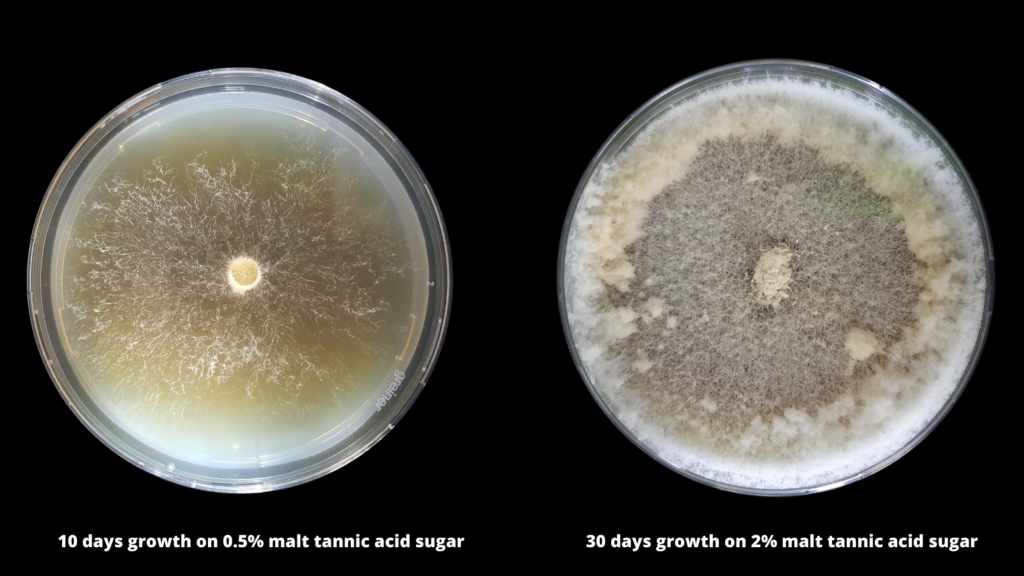

L. sulphureus is a heartwood-rotting fungus that finds its way into the non-functional wood at the centre of a tree. By producing a suite of enzymes it carries out the decomposition of this woody resource in a manner known as ‘brown-rot’. This is an ability only found in a small number of orders of the phylum Basidiomycota, and one considered to be the most recently evolved strategy for wood decomposition.

Brown-rot fungi modify lignin in the wood cell wall without breaking it down, altering it enough to allow decomposition of the cellulose and hemicellulose into sugars. This leaves behind characteristically brown and cubically cracked remnants of lignin that are easily broken down further by mechanical processes or weathering. L. sulphureus creates characteristic sheets of rubbery mycelium that form in splits and radial cracks as the wood decays, forcing the wood apart.

The crumbling lignin remnants, when returned to the soil, form part of the absorbent and nutrient-rich layer of humus in soil. Brown-rot fungi are especially important in the heart-rot of oak trees, with Fistulina hepatica (beefsteak fungus) and L. sulphureus being the most common species detected in our ongoing study of decay communities in standing oak trees. They are also the most common species fruiting from decaying heartwood in oak.

The decay of heartwood is an important and natural part of the ageing process for the tree and has several benefits for the tree host. The rotting heartwood, brought about by primary and secondary decay species and often aided by invertebrates, releases nutrients which are delivered directly to the roots of the tree. In some cases adventitious roots (those which grow from non-root tissue) form on the interior of a developing hollow to gain early access to this private food source.

Oak trees will often respond to heartwood decay by producing buttress roots, increasing the angle at which the trunk is connected to the ground, thus creating better resistance to high winds. In general, it is as if the tree had been adding into a savings account year-on-year to be used later in life and the fungi were helping to unlock those savings.

Observations so far indicate that this fungus is unable to attack living cells in the cambium of its host tree (the tissue layer linked to plant growth). But unfortunately, as with many saprotrophic species of fungi found on living trees, it is often mislabelled as a pathogen, masking the important relationship that this fungus has with trees and often resulting in unnecessary felling. Although non-pathogenic, L. sulphureus can nevertheless sometimes cause limb-loss or other structural issues in oak trees.

A boon for biodiversity

As mentioned above, the extensive hollows that L. sulphureus creates can support exceptionally biodiverse communities. Huge numbers of saproxylic invertebrates (dependent on dead or decaying wood), including rare beetles, bees and ants, plus a host of small mammals, bats, owls, and other birds, all make their homes and find their food in these dark crevices. It is this amazing engineering partnership between a tree and wood decay fungi that creates an incredibly rich habitat of hollows.

Even the fruitbodies of L. sulphureus can become rich habitats in their own right, offering food and shelter to many invertebrates, especially beetles such as Diaperis boleti and Eledona agricola.

In addition to its culinary value and ecological relevance, L. sulphureus has also been used in traditional medicine as a treatment for cough and other ailments. Modern studies have revealed its ability to produce many chemical compounds (e.g. phenolics, triterpenes, and polysaccharides) with various potential health applications including anti-inflammatory, antimicrobial, antioxidant, antihyperglycemic, antitumoral and immunomodulation activity.

Future genomic discoveries

The genome now produced for this species has the potential to help us resolve the cryptic diversity of this genus in the UK and to greatly expand our understanding of how these essential habitat-engineering fungi operate and interact in their environment. This information may be critical to our ability to protect the myriad organisms that rely on dead wood and tree-hollow habitats.

Moreover, genome data will allow further exploration of the potential medical and chemical applications that this species holds, potentially allowing the development of new medicines and biosynthetic pathways to help protect our futures.

This article was written by Richard Wright, Ester Gaya and Brian Douglas, members of the DToL fungi team at RBG Kew. It is adapted from an article originally published on the Kew website.